Abstract

Forty-five years of work with children has enriched my knowledge. Child development and psychology has made basic concepts of general psychology and abnormal psychology clearer. ‘Meanings’ have become more meaningful. It has made me a better professional; large number of communication and teaching skill has been the end result of such a long association with diverse groups of children who needed special care. Apart from professional skills as a clinician and as a teacher, it has made me a better person and a better parent. I have been fortunate to work with a large number and different groups of children who were in some way very special. Some were classified under various disabilities or diagnosed under different categories. I also had the privilege of working with different institutions, e.g., child guidance clinics run by a paediatrics department and a psychiatry department of a general hospital and a teaching hospital. Years of association with College of Special Work and Institute of Social Science have made me understand the very important facet of sociocultural influence on the development of human behaviour. I was further fortunate to work with children in closed and open institutions, residential care units and day care units, institutions where court committed children were observed, treated, trained and cared for, destitute children and delinquent children in remand homes, rescue homes and custodial care homes. I was fortunate to be part of the group which dealt with children who were in conflict with the law, belonging to diverse categories like street children, working children, child sex workers and sexually abused children. This paper is a reflection on experience gained over the decades.

Keywords: Absence of warmth and aggressiveness, Child development and psychology, Children’s influence on parents, Global ability of a child, Human socialisation, Hyperactive and Erratic children, I.Q. scoring patterns, Laterality training programme, Mammalian parental cycle, Motor training, Neonatal behaviour, Parental permissiveness, Parent-offspring relationship

Introduction

I love children. They have always fascinated me. My 45 years of work with children has enriched my knowledge. Child development and psychology has made my basic concepts of general psychology and abnormal psychology very clear. I have grown, developed and matured, living with various groups of children; my long association with them has resulted in considerable clarity and depth in understanding development of human behaviour both normal and abnormal. ‘Meanings’ have become more meaningful. It has made me a better professional; large number of communication and teaching skills have been the end result of such a long association with diverse groups of children who need special care. Apart from professional skills as a clinician and as a teacher, it has made me a better person and a better parent. I am convinced that my living with various groups of children and listening to them has been a continuous learning process.

I have been fortunate to work with a large number and different groups of children who are in some way very special. Some have been classified under various disabilities or diagnosed under different categories. I have had the privilege of working with different institutions, which cater to these children like child guidance clinics run by a paediatrics department and a psychiatry department of a general hospital and a teaching hospital. My years of association with College of Special Work and Institute of Social Science have made me understand the very important facet of sociocultural influence on the development of human behaviour. I was fortunate to work with children in closed institutions and open institutions, residential care units and day care units, institutions where court committed children are observed, treated, trained and cared for, destitute children and delinquent children in remand homes, rescue homes and custodial care homes. I was fortunate to be part of the group which dealt with children who are in conflict with the law. This group consisted of children belonging to diverse categories like street children, working children, child sex workers and sexually abused children.

What I Have Learned from Children

Concept of normal has always fascinated me. Large number of normal values and its variations makes generalisation so difficult. For example, hill tribe children are carried on the back of their mothers due to the hilly nature of the terrain. They learn to walk at only 2 years but turn into the best runners and climbers by their 3rd birthday. Best of development scales fail to cover such large variants in normal development pattern. It is more reliable and valid as age advances month after month. When we refer to Baroda norms and Mumbai norms, it only projects one’s difficulties in labelling research finding as Indian norms. One wonders – with such diversity of population distribution, with variation in ethnic, geographical, religious and sociocultural background, with different genetic patterns, child rearing practices and the way in which the child is born and brought up – what becomes of the ‘Indian norm’, which, according to me, is a myth. Years of experience in planning and implementation have convinced me that we do not need a national programme. What we need is socio-culturally-based local innovative individualised programmes.

Rural children are so different and superior in their motor development and urban children so different and superior in their mental development. As one has different I.Q. scoring patterns in Bhatia’s test for the literate and the illiterate, we do not have such different scoring patterns for different disabilities viz., mental retardation, cerebral palsy, deafness, blindness and multiple handicaps. It is only experience that helps the evaluation of such children by learning test after test and year after year – helping the evaluator’s judgment and final conclusion. One must admit that good judgment comes from experience; experience from poor judgment. What is to be noted is experience and learning are interwoven and not interchangeable. If you do not have an inquiring mind and an observing eye, you will never develop sound clinical judgment which one expects from years of experience.

Global ability of the child dictates many therapy programmes. It is of vital importance to know the specific ability before planning training and treatment programmes. The therapist must be able to evaluate the child’s ability at different levels of functioning to give individual therapy at the child’s developmental level. It is training, teaching and integrating all the time as development unfolds. Frustration and failures of the child will give the therapist an indication of shortcoming in his management and therapy. Child reflects and rewards good therapy and a good programme. Optimum therapeutic outcome is achieved only if a training programme is within child’s ability and natural developmental stage.

Any change in development pattern must compel one to review all the influencing factors. Laterality development is an ideal example of how child monitors and dictates a therapeutic training programme. Laterality development may change in early years due to ischaemic insult to the brain; this may result in cross laterality or change in laterality. Child is the best guide to determine laterality-training programme in the first 6 years of its life. Child’s preference is final. No expert can predict or programme laterality. Forcing laterality change will result in stammering, bedwetting, reading-writing slowdown, nail-biting, regressive behaviour and negative accentuation of existing personality traits. Adult learns with time and follows the right programme, which is dictated by a child’s preference. By following the child’s preference one sees complete and prompt reversal in all the above-mentioned behaviour disturbances. Following the child’s preference helps faster establishment of laterality and development or change in laterality development. It is very difficult to visualize impact of management or mismanagement of one developmental area disturbing child development in general e.g., motor and laterality development having direct impact on personality, emotional, mental, speech and language development; not to talk of retardation or regression in child’s behaviour.

Motor training facilitates mental development. Importance of all motor activity like play activity is so ill understood that family and society behave as if they are contradictory, not complementary. Motor activity promotes mental growth and socialisation. The amount of relaxation and recreation achieved is so much that all adults need to reorient their lifestyle to accommodate various motor activities. A joint play activity by parents and the child gives the best result for both, a classical bi-directional benefit.

Role of play therapy in giving considerable information about child’s ability and disability is under-utilised. The therapist can arrive at a detailed diagnostic work-up by longitudinal focused observation. Preventive and promotive aspects can be objectively recorded and rated in the areas of mental emotional personality and social development. ‘Each one teaches one’ slogan is most effectively used in child-to-child learning and child to adult learning. The therapist can learn so much from a group of hyperactive children, how they manage, guide, control and correct each other in group settings.

Every child has visual and auditory preferences and learning style. The child sets preference and priority, e.g., deaf child is superior in punctuation and digit reverse phenomenon, both being visual learning processes. Normal hearing child has auditory language which help him learn many more things, but with distinct disadvantage of audio–visual learning which can be appreciated only when therapist learns about gains of total deafness at birth and 1st year of life. It important to know that a therapist can diagnose deafness only by Goddard Form Board Test where normal and deaf children will achieve same result of success in a given time, scoring equal marks; the only difference being more number of motor errors in completion of the given task by the deaf than the normal. The therapist can diagnose the deafness during psychometric evaluation, which gives him joy and delight that such simple clinical observations can give such vital diagnostic clues. It is an effective and easy method which saves time and money. Its utility at school, community and rural level is significantly high where instrumentation and expertise is not easily available.

While working with children having severe and multiple disabilities, the therapist alters his concept of how much can be done so that he will never have a nihilistic approach and will never say, ‘Nothing can be done’. The family is also a therapeutic team. The therapist, the child and the family can achieve many goals by each other’s complementary efforts.

Technological advance and growing knowledge in neuroscience have been of little help when it comes to application in management of multiple disabilities. The therapist will have to learn from each such individual child and review and reframe his therapy. The therapist has his own limitations. It is the child who sets his own limits; omnipotence of therapy and therapist is gradually changed to a level of acceptance wherein one accepts one’s inability to mould and manipulate the child and his environment.

Effective and innovative programmes are child-centered, child-preferred, child-dominated and at times child-dictated. ‘Catch them young, as young as possible’ and ‘Early intervention and intensive stimulation’: Both these principles are applied in adult psychiatry with best therapeutic result and excellent prognosis.

Effective functioning of the motor system results in least dependency in adult life. Motor dexterity results in healthy self-concept and sound personality development. It facilitates socialisation and integration. Reduced motor ability and disability results in social withdrawal and total isolation of the child and his family. They continue to live with the guilt, denial and boredom. Parents who learn maximum from their child and attain objectivity about their children are in a better position to coordinate and apply all the facts to the best advantage of the child. The same principle applies to the therapist.

Commonly Observed Bi-directional Phenomena (Child’s Effects on Adults)

We expect parents to influence their children. People who live together usually affect each other, but what is often overlooked is the extent to which children influence their parents and other adults–the very children they are trying to rear, themselves mould parents and other caregiving adults. It is very important to recognize the need to examine the other side of the equation. It has been shown that the direction of effects, adult to child or child to adult, is unclear in most of the finding from the past 40 years of research. It is unlikely this viewpoint would receive much empirical attention, or become assimilated into theory until it had been translated into a set of a coherent alternatives to traditional thinking. As yet, with few notable exceptions, most advocates of the new perspective have focused upon the logical possibility that the parent-offspring/adult-child relationship could be reciprocal without providing the substantive content needed to replace the possibilities with actualities. Some of the most provocative models of reciprocity in the caregiver-offspring relationship, as well as the most thoroughly documented analyses of offsprings’ effects on parents, or other adults, have emerged from work on animals. It is high time to look at the ‘other side of the coin’ which shows how the young initiate, maintain, differentiate and terminate adult behaviour. This is quite contrary to behaviour scientist Watson’s belief in a ‘Unidirectional adult–child interaction’.

Children’s influence on parents, even when acknowledged in the past, has been treated as if it were unimportant. The very best data from studies of human socialisation can often be interpreted as showing effects of children on parents rather than the other way around. A review of literature on other mammals suggests that in evolutionary history, the young mammals were also the ones who led their elders into new territory, ate new food and accounted for the adaptation of the species into a new environment.

History

From records of the ancient Mediterranean civilization, we find that parents and other adults were highly responsive to the distinctive characteristics of infant and young children. The power or importance of the young can be seen in the writing of philosophers and religious leaders. Then, just as now, were those who saw a potential threat to the morality and political structure of adult society in the spontaneity and capability for innovation shown by the young. There were also the optimists, educators who saw ‘good’ seeds that should be left to flower and develop in their own beautiful way. In the child’s development, scientists, too, have variously seen the history of man’s evolution: the emergence of biological forces in the form of the battle of instincts against suppressive social structure and an imprinting process in which parents and educators registered their imprint at will by using principles of learning. All in all, if we did not know better, we might be inclined to say that down through the ages, the child has been an excellent Rorschach ‘inkblot’ in which anyone can see whatever one wants.

A moment’s reflection will tell any adult who has had more than casual contact with a small child that the child – even an infant – can exert definite and sometimes very strong influences on the adult’s behaviour. Is the child only recognised as an enjoyable object that is also necessary to complete a family, or do members of a society also see in the child an inspiring influence on the society’s destiny? It is important that adults recognised the specific contribution made by the young to their larger social group, neighbourhood and community, even culture.

Autonomous, emergent structures in infants

Reaction or responses to children that are seen by the adults as originating within the adult probably reflect the adult’s conception of the child. Extensive research attention to infancy in the 1960’s filled in the theories with facts on early perceptual and cognitive capabilities and it became apparent that the approach to socialisation that ignored these capabilities had been relatively barren of result. It had become increasingly apparent that infants as well as young children have certain inbuilt, or relatively autonomous, emergent structures which they react to and which affect the things and people around them.

Whatever the reason for the lag between various branches of behavioural science as a result of over 40 years of careful controlled experimentation, the comparative literature now contains many thoroughly documented studies of the ways in which the young influence caregiver behaviour; and several provocative, descriptive models are available for conceptualising the dynamics of the parent-offspring interaction in mammals (Rheingold, 1963).[15] Biological theory is moving towards quantitative models of animal social dynamics, one of which endeavours to predict the timing of weaning by evaluating the active role played by the young as well as the mother in the parent-offspring relationship (Trivers, 1974).[17]

To address the full complexity of the human socialisation process, it is necessary to free ourselves from ideological fetters whose origins reach back centuries. We must fully appreciate that it no longer necessary to take so extreme a stand on the malleability and educability of children that we find ourselves unable to recognize the ways the children can educate adults.

There is some truth in Peter De Vries (1954) quip: ‘The value of marriage is not that the adults produce children, but that children produce adults’. We can accept the possibility of children making their own contribution to the stream of development and to the changing parent-child social system, without indicating approval of that period in the history of sociology and psychology in which instincts were sought in every human behaviour pattern and in which biological determinants were hypothesised for national, ethnic and individual differences.

The young are a part of the environment of adults and parents and thus must be accepted as a source of stimuli. We should be prepared to accept substantial control of parental behaviour by the young on this ground alone (Watson, 1966).[18] Even the youngest of the infants, the new-born that has no behavioural repertoire traceable to social interactions, is in some respect much more powerful than the young parent. Young parents are at the mercy of a cry and further, cannot escape the compelling quality of the infant’s facial expression and its helpless thrashing movements once the cry has brought them within visual range.

Parents with a first-born seem not only overwhelmed with their new responsibilities but also somewhat helpless and confused. In many respects, they appear to be much less powerful than the infant whose behaviour is remarkably well-organised to produce a given result. The amount of attention and the number of responses directed to the infant are enormous – out of proportion to its age, size and accomplishment.

A theoretical orientation towards parenting-effect could find confirmation in the fact that the mother of identical quadruplets who were schizophrenic was uniformly extreme in restrictiveness with her daughters. On the other hand, they might find it awkward trying to account for the fact that she was not uniform in affection unless they paid some attention to the possibility that there were non-genetic congenital differences between the infants that could have affected the mother (Schaefer, 1963).[16]

Learning disorder and disabled difficult defective children

In a research project, the families of the children with a learning disorder were rated as more disorganised and less stable emotionally than the control families. Denial, guilt, rejection and hostility are commonly observed in parents of disabled children. Deathwish and extended suicide are not a very uncommon adult response due to helplessness, hopelessness and worthlessness experienced during continuous painful struggle in care and management of a difficult, disabled and defective child. Women who have difficult infants or damaged infants often suffer from loss of self-esteem (Frank, 1965).[3]

Some inkling of bi-directional effects emerged from the clinical studies in which parents reported their perception of the child as a cause of the problem. Many of the parents and especially grandparents felt that they have been abused by the child, not that they had abused the child. Deviance in the child was at least as substantial a factor in explaining the incidents as deviance in the parents. Constant fussing, a strange and highly irritating cry and other exasperating behaviour were frequently reported for one child in the family singled out for battering (Gill, 1970).[5]

A sequence analysis of adult–child interactions in a nursery school setting uncover the fact that adults return more quickly to initiate positive contacts with the children who, in the previous interaction, showed interest or compliance. When children’s behaviour was manipulated by role–playing or by designing special tasks, effect on adult or parent’s behaviour could be detected. When children, who differ in speech characteristics, were placed in the interaction situation with adults, the speech of the adults was also affected.

The parent is much more mature than the child, has more power and has a behaviour pattern more closely approximating the adult pattern of the culture. It would be a mistake to simplify the parent-child interaction by saying that the young child socializes the parents. But children start approximately 50% of interaction; indicating again that the greater maturity of the parents is no basis for assuming that the parents initiate most of the interaction that lead to socialisation (Wright, 1967).[19] The empirical evidence is that there is a balance related to starting an interaction; neither parents nor child dominates the situation.

There is a clear inequality and asymmetry in the relationship of parents and children, namely that involving intentional behaviour. The younger the child, the less likely it is that the child is consciously controlling parental behaviour in order to achieve certain consequences. The quality and extent of the intentional behaviour gradually develops in the 2nd year so that this element increasingly comes to bear on parent behaviour; none the less, it is clear that throughout the early years of child rearing, intention in much more characteristic of parents than child behaviour (Wolff, 1960).[20]

The steady and persistent resistance of children to some parental objectives may lead to the eventual abandonment of an objective, despite the fact that the parent dominates more specific interaction bouts. Children can also exercise control through a means that is sometimes overlooked as a source of power-appeal. Parent-child interaction occurs in a reciprocal special system in which much of the progress towards cultural norms involves mutual adjustment and accommodation. Parental control through the power and long-range intentional behaviour is offset to a certain extent by children’s sheer activity in starting interactions, their resistance to domination and their inherently appealing nature (Wright, 1967).[19]

Parents of hyperactive, erratic children

Parents of hyperactive, erratic children would be more likely to respond, in rough order, with distraction, holding, prohibiting verbalisation and physical punishment, having had past experience that did not positively reinforce the use of reasoning, threat of withdrawal of love and appeals to personal and social motives.

Modelling is not a one-way process; children may serve as models for the sex-role of their parents as well as emulating them and their own peers and siblings. These finding undermine the traditional assumption that sex roles are learned chiefly or exclusively through the child’s identification with the like–sexed parent; permissiveness by parents tends to be related to aggression, assertiveness, achievement and independence in children. In contrast, parents who are restrictive may tend to have children who are somewhat more dependent, compliant, conforming, fearful and polite (Mischel, 1970).[13]

Both the child’s lack of competence and inability to use skills (because of fear or an overly intense relation to an adult), or perception of a child’s lack of competence and failure to apply himself to a task leads to lower limit parental control behaviour involving urging, prompting and directing as well as more protective behaviour (Maccoby and Masters, 1970).[11] Dependent children tend to have rejecting parents because they are dependent. Their dependent behaviour, beyond a tolerable level of intensity and frequency that is graded according to age, alienates parents. In correctional studies, it is not possible to determine how important a factor this is. This interpretation is an increasingly likely parental response of rejection, as child behaviour increases in intensity from conformity through dependency to word passivity. Sometimes, adults promote dependency, which may be the result of a child’s refusal to self–help and respond to the promotion of independence. Insecurity and degree of role reversal during adolescence bring out critical adult behaviour, e.g., to label the young as a rebel. Congenital assertiveness in children who were aggressive with peers activated upper limit control in parents so that their response escalated from verbal abuse to the extreme of physical punishment.

In these various factors, let us consider the behaviour of the child as a constant. Parents, however, are not immune to their children’s behaviour, and their response to a particular act may be influenced by the history of their interaction with the child. The parent who uses severe punishment may have begun with soft words, which failed to achieve their objective of aggressive control. Children differ in their predisposition to aggression and their docility. These variations in aggressiveness may evoke from the parent some portion of that very punitive behaviour which may be assumed to be their antecedents. Although one can exaggerate the influence of the child’s aggression upon the parent’s disciplinary practice, the possible contribution of the child’s behaviour to the parent-child interaction has been largely ignored and some attention to this dimension is required.

Association between the absence of warmth and aggressiveness

The association between the absence of warmth and aggressiveness in the child is not necessarily unidirectional. The child’s aggressiveness may elicit rejecting response from the parent, which in turn fosters further aggression, thereby establishing an unhappy Cycle of rejection–aggression. The important point is that the child’s aggression, regardless of its origin, must be considered as having the capability of affecting the parent (Feshbach, 1970).[2]

The child’s own characteristics affect not only the disciplinary technique utilised but also the extent to which the parent’s goal can be realised. Moral development is forged by many specific situations out of the interaction of the child’s short–term and parent’s long-term goals.

There is sufficient evidence to assume congenital contributions to impaired sensory–motor development, impulsiveness, assertiveness and social response in children. These congenital contributions are used in conjunction with a control theory model in which it is assumed that excessive and inappropriate child behaviour induces upper–limit control behaviour from parental repertoires; and by contrast, child behaviour that is below parental standards induces lower-limits parent control that act to stimulate behaviour. Parental repertories are hierarchically and sequentially organised. Child’s behaviour ‘keys in’ specific response or patterns from parental repertoires.

The association of parental permissiveness with child attributes, such as assertiveness, achievement and independence, identified by the culture as ‘masculine’, is interpreted as involving neither upper nor lower limit control behaviour. The parent is presumably reacting to appropriate capability and self-sufficiency by giving the child a free rein. The often cited association of parent restrictiveness and rejection with child dependence is assumed to be due to a lower-limit control reaction involving urging, prompting and directing in response to the fact that the child’s performance is below parental standards.

The association of rejection, inconsistency and severe physical discipline with child aggression is interpreted as an upper-limit control reaction to extremely aggressive child behaviour. The association of parental power assertion and low guilt in the child is assumed to be due to congenital contributors to fast-moving, impulsive, situationally controlled behaviour that induces more power assertion in the parent and does not favour internalisation. The association of affection and inductive parent techniques with high guilt in the child is assumed to be a response to person-orientation and social responsiveness in the child.

Further progress in socialisation research requires that parent and child can be considered as a true social system with responses of each serving as stimuli for the other (and changes in each having some likelihood of affecting the other).

Excessive crying in infants

Excessive crying in infants can induce tension, anxiety and inadequacy in the maternal role. Leach and Costello have reported a unique effort to apply the classic twin study approach to the problem of determining effects of infants on their mothers. Within pair differences in infant behaviour and maternal handling were to be contrasted for monozygotic and dizygotic pairs on the assumption that monozygotic twins behave more similarly to each other and thus will be treated more similarly by their mothers (Leach and Costello, 1972).[8] One concern with this application of twin studies is that mother’s greater similarity of treatment of monozygotic twins might be due to knowledge of their zygosity rather than a response to behavioural similarity.

Specific maternal behaviour could be accounted for more by the infant’s behaviour than by the mother’s general maternal style or attitude. The relation between infant state and maternal response might reflect a genetic similarity between mother and infant or a common condition induced by some perinatal factor (Levy, 1958).[9] Children may start about as many interactions as parents, but if a conflict exists between parent and child, the outcome may more often reflect the fact that the parent’s potential as a reinforcing agent far exceeds that of the child (Hoffman, 1975).[7]

Mothers of firstborns and only child were more extreme than mothers of children from other birth orders; there was greater support when the child succeeded and withdrawal of the support when the child was represented to her as failing (Merrill, 1946).[12] Parents of boys who were high achievers encouraged their sons more and interfered less than parents of low achievers in the very difficult tasks that had been selected so as to make most children struggle. It was found that fathers and mothers controlled more and physically and verbally interacted more when children acted dependent (Osofsky and O’Connell, 1972).[14]

Much of the neonatal behaviour – the crying, mass movements and recurrent startles during sleep appears to arise from endogenous stimuli. Infants are organised for activity before they become organised for reactivity. The mother is acted upon by the infant, whose behaviour plays a strong role in inducing caregiving and social interactions, as well as differentiating these modes of interaction. Towards the end of the year, the infant’s behaviour becomes highly reactive in many complex ways. This change does not occur in all areas in a single month but steadily in each of the domains of development at different times. By this time, the mother has acquired the capability of managing the infant and influencing its behaviour, so that to a much greater extent, their interaction is reciprocal in nature (Livingston, 1967).[10]

Mother and infant in physiological interaction

The mother and infant have been in physiological interaction during the entire process of pregnancy and even in a limited behavioural interaction, consisting of responding to the movements of each other. Some mothers respond to the crying infant because they wish to provide comfort and relief; others may respond mainly because the cry is a noxious stimulus they wish to terminate. In either case, the infant’s cry apparently leads to maternal behaviour that removes the activating circumstances. The infant contributes to caregiving by informing the caregiver about preferences and limits. If the mother is sufficiently sensitive to her infant, she may even come to recognize that frowns shown during active sleep will forecast awakening and signs of hunger (Emde, Gaensbauer and Harmon, 1976).[1]

The successive emergence of new behaviours, regardless of the specific behaviour involved, is exciting and interesting to the parents. If something new is happening each week or so, the caregiver’s motivation to remain in the behaviour interaction system with the infant receives general strengthening (Gewirtz, 1961).[4] Parental behaviour involves a variety of responses not all of which are unique to caregiving. The behaviour of both parent and child is matched to form a complementary series and is often buffered against physiological and environmental fluctuations. As the young mature, the match must be maintained, involving changes in both caregiver and young. Just as offspring behaviour is modified by interaction with the parent, parental behaviour changes as a result of caring for the young.

Mutual exchange of stimulation

Examination of the mammalian parental cycle from conception through termination of the caregiving relationship reveals that the young play an important part in controlling behaviour of the caregiver in every phase. This does not mean that the parent is simply the pawn of the young, nor does it imply that the offspring of every species plays an equally important role in all aspects of the parent-offspring relationship. It means that the development of most of the parent-offspring relationship depends upon input from the young. The control of short-term interactions between parent and child involves a mutual exchange of stimulation. Depending upon the species and the nature of the exchange, either party may make the first move to initiate, maintain, differentiate or terminate a bout of interactions. Both quantity and quality of child stimulation are important determinants of the quality, amount and duration of the response from the parent.

It is quite common for individuals who have assumed a caregiving role to experience a change in social status within their group directly or indirectly as a result of their relationship to the young. There are many examples of the ways in which the presence and interactions of the young may cause a widening of parental social relationships. Although these changes obviously reflect many different causes, they do not indicate that the young can affect group cohesion (Harper, 1975).[6] The prospect or presence of young affects not only the care-giver’s relationships but caregiving can also influence the pattern of interaction and responsibility within the wider group and sometimes across groups. Although such offspring effects are clearly no mirror images of parent affects, they nevertheless indicate that unidirectional models cannot adequately capture the full complexity of the caregiving relationship.

Experts who have reviewed specific areas of the vast literature on human socialisation have in the last few years come to recognize that a unidirectional approach involving exclusive attention to the effects of parents is no longer defensible. The child plays a substantial role in shaping the process by which any particular end state is reached.

You know your child. You grow with your child. Your child will help you and teach you to help any child.

Finally, let me end this paper by a quote:

Children when they are little make their parents fools; whey they are great, they make them mad. -George Herbert.

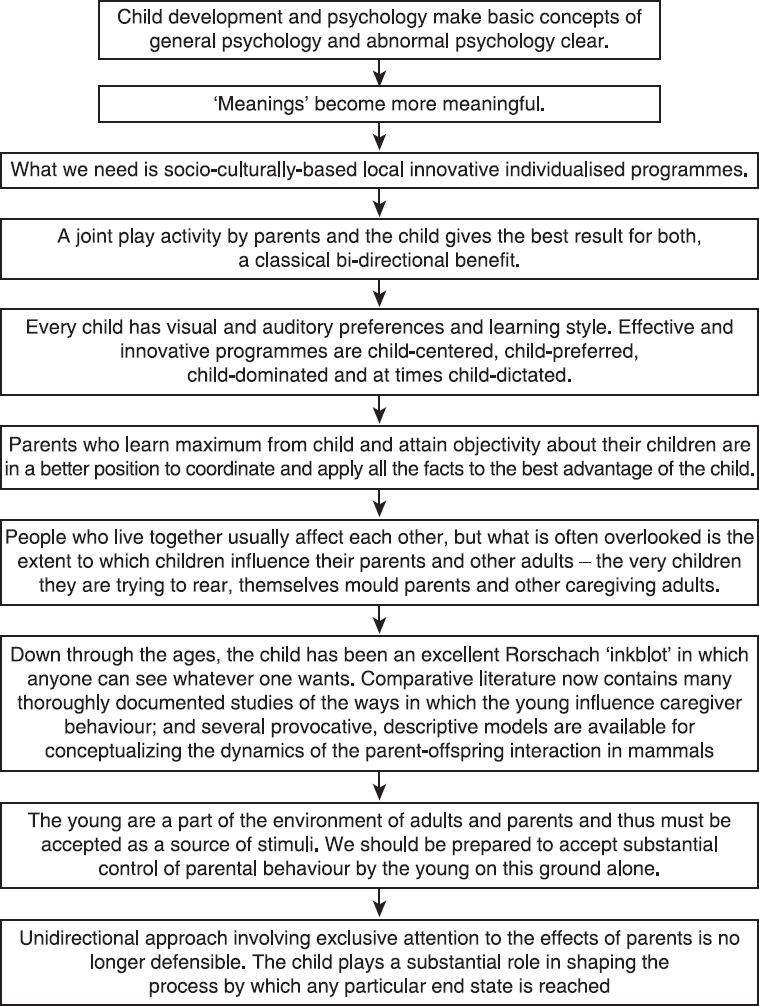

Conclusions [Figure 1: Flowchart of Paper]

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the paper

Child development and psychology have made my basic concepts of general psychology and abnormal psychology very clear. ‘Meanings’ have become more meaningful. What we need is socio-culturally-based local innovative individualised programmes. A joint play activity by parents and the child gives the best result for both, a classical bi-directional benefit. Every child has visual and auditory preferences and learning style. Effective and innovative programmes are child-centered, child-preferred, child-dominated and at times child-dictated. Parents who learn maximum from a child and attain objectivity about their children are in a better position to coordinate and apply all the facts to the best advantage of the child. People who live together usually affect each other, but what is often overlooked is the extent to which children influence their parents and other adults. The very children they are trying to rear, themselves mould parents and other caregiving adults.

Down through the ages, the child has been an excellent Rorschach ‘inkblot’ in which anyone can see whatever one wants. Comparative literature now contains many thoroughly documented studies of the ways in which the young influence caregiver behaviour; and several provocative, descriptive models are available for conceptualising the dynamics of the parent-offspring interaction in mammals.

The young are a part of the environment of adults and parents and thus must be accepted as a source of stimuli. We should be prepared to accept substantial control of parental behaviour by the young on this ground alone. Unidirectional approach involving exclusive attention to the effects of parents is no longer defensible. The child plays a substantial role in shaping the process by which any particular end state is reached.

Take Home Message

We should be prepared to accept substantial control of parental behaviour by the young. Therefore, a unidirectional approach involving exclusive attention to the effects of parents is no longer appropriate.

Questions that this Paper Raises

Where is child psychiatry headed as a sub-specialty?

How relevant is the bi-directional model in understanding child behaviour, and modifying faulty parent-child interactions?

How relevant are cross-cultural and ethological studies to child psychology?

What are the areas of connect between child psychology and child psychiatry?

About the Author

P. C. Shastri MD was Professor and Head, Department of Psychiatry at BYL Nair and TNM College, Bombay Central, Mumbai. He continues as Honorary Professor in Psychiatry at Anabatic Hospital in Andheri and the Indian Armed Forces Medical Services, (INHS Ashwini), besides being in private practice. He has been the Past President of the Bombay Psychiatric Society, 1985-1986, President of the Indian Psychiatric Society, 2008-2009, and President, SAARC Psychiatric Federation, 2008-2009. The Bombay Psychiatric Society has awarded him the Dr. S. M. Lulla Oration Award in 1998 and Dr. V.N. Bagadia Lifetime achievement Award in 2007. He was also honoured with the Dr. L.P. Shah Oration Award by the Indian Psychiatric Society’s West Zone in 2007. Child psychiatry continued to remain his abiding area of interest.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Declaration

This is my original unpublished work, not submitted for publication elsewhere.

CITATION: Shastri PC. Child: A Learning Model and a Bi-directional Phenomenon. Mens Sana Monogr 2015;13:31-46.

Peer reviewer for this paper: Anon

References

- 1.Emde RN, Gaensbauer TJ, Harmon RJ. Emotional expression in infancy: A biobehavioral study. Psychol Issues. 1976;10:???. 1, Monograph 37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feshbach S. Aggression. In: Mussen PH, editor. Carmichael’s Manual of Child Psychology. 3rd ed. New York: Wiley; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank GH. The role of the family in the development of psychopathology. Psychol Bull. 1965;64:191–205. doi: 10.1037/h0022427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gewirtz JL. A learning analysis of the effects of normal situation, privation and deprivation on the acquisition of social motivation and attachment. In: Foss BM, editor. Determinants of Infant Behavior. Vol. 1. New York: Wiley; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gill DG. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1970. Violence Against Children. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harper LV. The scope of offspring effects: From caregiver to culture. Psychol Bull. 1975;82:784–801. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman ML. Moral internalization, parental power, and the nature of parent-child interaction. Dev Psychol. 1975;11:228–39. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leach PJ, Costello AJ. A twin study of infant-mother interaction. In: Monks FJ, Hartup WW, Dewwit J, editors. Determinants of Behavioral Development. New York: Academic Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy DM. Behavioral Analysis: Analysis of Clinical Observations of Behavior as Applied to Mother-Newborn Relationship. Spingfield, III: Charles C. Thomas. 1958 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Livingston RB. Brain circuitry relating to complex behavior. In: Quarton GC, Melnechuk T, Schmitt FO, editors. The Neurosciences. New York: Rockefeller University Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maccoby EE, Masters JC. Attachment and dependency. In: Mussen PH, editor. Carmichael’s Manual of Child Psychology. 3rd ed. New York: Wiley; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merrill B. A measurement of mother-child interaction. J Abnorm Psychol. 1946;41:37–49. doi: 10.1037/h0055839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mischel W. Sex-typing and socialization. In: Mussen PH, editor. Carmichael’s Manual of Child Psychology. 3rd ed. New York: Wiley; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osofsky JD, O’Connell EJ. Parent-child interaction: Daughters’ effect upon mothers’ and fathers’ behaviours. Dev Psychol. 1972;7:157–68. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rheingold HL, editor. New York: Wiley; 1963. Maternal Behaviour in Mammals. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaefer ES. Parent-child interactional patterns and parental attitudes. In: Rosenthal D, editor. The Genain Quadruplets. New York: Basic Books; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trivers RL. Parent-offspring conflict. Am Zool. 1974;14:249–64. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watson JS. The development and generalization of “contingency awareness” in early infancy: Some hypotheses. Merrill Palmer Q. 1966;12:123–35. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright HF. New York: Harper & Row; 1967. Recording and analyzing child behavior. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolff PH. The developmental psychologies of Jean Piaget and psychoanalysis. Psychol Issues. 1960;2:1–178. [Google Scholar]