Sasidharan K. Rajesh, Judu V. Ilavarasu, T. M. Srinivasan, H. R. Nagendra

Mens Sana Monogr. 2014 Jan-Dec; 12(1): 139–152. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.130323

PMCID: PMC4037893

Abstract

Stress is recognised as the most challenging issue of modern times. Contemporary science has understood this phenomenon from one aspect and Indian philosophy gives its traditional reasons based on classical texts. Modern science has recently proposed a concept of perseverative cognition (PC) as an important reason for chronic stress. This has shown how constant rumination on an unpalatable event, object or person leads to various lifestyle disorders. Similarly classical yoga texts like the Taittiriya Upanishad, the Bhagavad Gita, and the Yoga Vashistha describe stress in their unique ways. We have here attempted a detailed classification, description, manifestation, and development of a disease and its management through these models. This paper in a nutshell projects these two models of stress and shows how they could be used in future for harmonious management of lifestyle disorders.

Keywords: Pañca kośas, PC, Perseverative Cognition, Stress, Yoga

Introduction

Stress in varying degrees has become a part of everyone’s life due to a shift from traditional to modern lifestyle. Stress may be best defined as a psychophysiological process, usually experienced as a negative emotional state, resulting from physical or psychosocial demands (Agarwal and Marshall, 2001[1]). Stress can be categorized in several ways (Larzelere and Jones, 2008[13]): Duration (acute/chronic), domain (physical/psychological), and severity (traumatic/daily hassles). Stress produces both adaptive and maladaptive effects on the physiological system. The burden of chronic stress can cause inhibition of neurogenesis, disruption of neuronal plasticity, even neurotoxicity (McEwen, 2007[15]). Further, accompanying changes in personal behaviour due to chronic stress cause wear and tear in the body (“allostatic load”), which in turn alters physical and mental health (Juster et al., 2010[8]).

Contemporary science has been greatly influenced by matter-based paradigms, while classical Indian thought has emphasised the role of consciousness-based approaches. Matter-based paradigms are rooted in technological advancement, while consciousness-based approaches have their roots in ancient Vedic literature. The two are not mutually exclusive, as both are interdependent and play an equal role in understanding aspects of the world (Nagendra, 2010[11]). An amalgamation of eastern and western concepts would give deeper insights to help face the present day demanding situations.

Perseverative Cognition (PC), an emerging idea from modern science, and essential concepts from classical yoga texts like the Taittiriya Upanishad, the Bhagavad Gita, and the Yoga Vasistha, are reviewed here, and a conceptual framework of stress is presented. Further, this article intends to explain the cause of stress and propose a framework to explain development of illness from stress.

What is perseverative cognition (PC)?

In recent times, perception of an event is given prominence to study individual’s response to a given environmentally demanding situation. A gradual shift in the consensus from external control to internal control has paved the way for new researches. This is especially supported by emerging concepts in stress research like the concept of Perseverative Cognition. Mind wandering is considered as a default mode of functioning of the brain. However, the state of mind wandering sometimes shifts to the state of repetitive thinking and leads to a prolonged and aroused state of physiology (Brosschot et al., 2005[2]). This phenomenon is named Perseverative Cognition (PC).

Model of stress response according to perseverative cognition theory

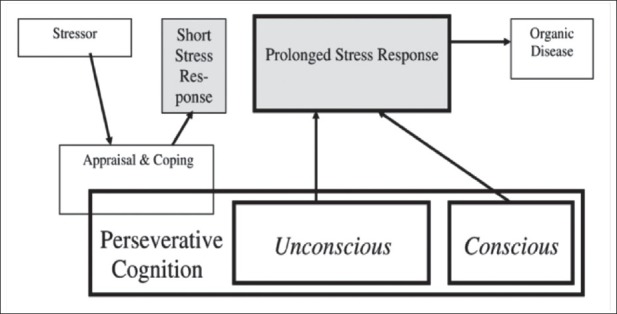

PC hypothesis has provided valuable insight into the link between stressful events, psychopathology, and somatic health (Brosschot et al., 2005[2]). This can be explained as shown in the following schematic diagram [Figure 1] (Brosschot et al., 2010[3]).

Figure 1.

The extended Perseverative Cognition Hypothesis model, adapted, with permission, from Brosschot et al., 2010[2]

According to the above model, when the individual copes well with stressors, it leads to short stress response and the recovery is quite fast. However, when appraisal results in ruminating and worrying responses (PC), it may lead to prolonged stress response, which includes enhanced arousal of physiological and psychological systems. Perseverative Cognition causes delayed recovery period (Larsen and Christenfeld, 2010[14]), which condition may lead to psychosomatic ailments/organic diseases. The amount of control executed in this situation is different in different individuals. As seen in this model, PC can be unconscious or conscious. Unconscious PC includes constant rumination without much awareness. Loops of thoughts happen without the awareness of the individual. Handling unconscious PC is more challenging than conscious PC.

Prolonged and improper physiological activity is considered a direct outcome of stress and it further leads to psychosomatic ailments. For every stressor that we face in our life we form a mental representation in the form of imprints, and this is stored in our cognitive repository. It has been found that activation of these mental representations causes severe damage which could be more than the actual stressor itself. This process may become long lasting and even continue during sleep. Many times these stressors can be anticipatory worry or rumination i.e., a sort of worry towards a situation which has not happened but has formed only in our mind. The term prolonged perseverative cognition includes all physiological responses that do not occur when the stressor is introduced. According to Brosschot, there are two bases for PC:

There is slow recovery after the stressor has been removed or continued autonomic activity before the stressor was introduced, just in anticipation of future events.

We form mental images of stressors and activate them irrespective of the presence of the actual stressor. This is called perseverative cognition.

Unconscious perseverative cognition is a major source of concern. Brosschot, Verkuil, and Thayer (2010[3]) have found out that conscious worry or conscious perseverative cognition is only explaining a part of the variance in stress response, and more than 50 percent is yet to be explained. There are stronger reasons to consider that this major portion of unexplained variance could come from the unconscious domain, as most of our daily activities are controlled by automatic processes without our conscious awareness. Hence in unconsciousness perseverative cognition, mental representations of stressors are activated without conscious awareness and they could cause prolonged physiological activities creating autonomic imbalances, and further, the development of various psychosomatic ailments.

Management according to Contemporary Science (McEwen, 2007[15])

Brain-Centered Interventions such as lifestyle modification

Pharmaceutical agents which counteract some of the problems associated with being stressed.

Moderate physical activity.

Social support at an individual level

Ancient Indian Concept: The five layers of our existence (Pañca kośas)

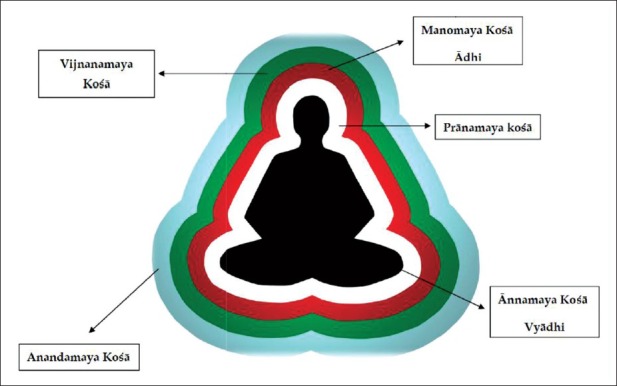

The Upaniṣads are a culmination of Vedic knowledge. The Taittiriya Upaniṣad discusses five levels of existence in the human condition (Chinmayananda,1992[4];. Nagendra, 2010[19]). The grossest and the outermost, the physical frame, is called the annamayā kośa, followed by the prāṇamayā kośa, manomayā kośa, vijñananmaya kośa, and the subtlest, the ānandamayā kośa [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Five sheaths (païca koŚas)

The annamayā kośa refers to the gross physical body which is a sheath sustained by food. The second subtler sheath is the prāṇamayā kośa, the sheath of energy body, featured by the predominance of prāṇa, the life principle, which flows through invisible channels called nadis. The next sheath in order of subtlety is manomayā kośa — the sheath of sensory capacities (emotions dominate and start governing our actions). Next is the vijñananmaya kośa — the sheath of cognitive function (power of discernment and discrimination predominates). Finally, there is the ānandamayā kośa — the shealth of blissfulness. Further, the five kośas can be classified into three groups — the physical (annamayā kośa), the subtle (prāṇamayā kośa, manomayā kośa, vijñananmaya kośa), and the causal (ānandamayā kośa) (Chinmayananda, 1992[4]; Nagarathna and Nagendra, 2001[17]).

Model of stress response according to classical Yoga texts

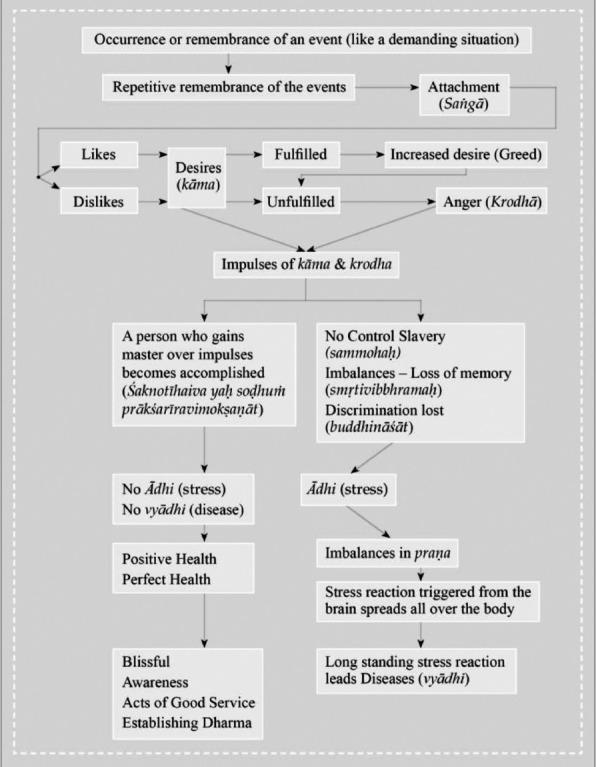

The Classical Yoga texts model of stress is explained as imbalance in different kośas. In waking state, occurrence of an event or demanding situation results in repeated thinking and further leads to attachment (sangah). Intense attachment (kāma) in its turn, leads to an avalanche of thoughts (strong likes and dislikes). When this avalanche of thoughts is unfulfilled, it transforms into intense anger (krodhah):

Dhyāyato viṣayān puṁsaḥ saṅgasteṣūpajāyate |

Saṅgāt sañjāyate kāmaḥ kāmātkrodho’bhijāyate |

Bhagavad Giįa|2|62||

[When a man thinks of the objects, attachment for them arises; from attachment desire is born; from desire anger arises (Sivananda, 2013[25])]

Intense Kāma and Krodha set out an involuntary impulse in the vijñananmayakośa:

śaknotįhaiva yaḥ soḍhuṁ prākśarįravimokṣaņāt |

Kāmakrodhodbhavaṁ vegaṁ sa yuktaḥ sa sukhį naraḥ ||

Bhagavad Gįta|5|23 ||

[He who is able, while still here (in this world) to withstand, before the liberation from the body, the impulse born out of desire and anger — he is a Yogi, he is a happy man (Sivananda, 2013[25])].

For a person who is able to withstand the impulses born out of desire and anger, all the actions will be governed by total knowledge based at the vijñananmaya kośa. Hence there will not be any adhi (stress) and the person achieves a state of perfect mental health. Those who do not have mastery over involuntary impulses due to desire and anger, continue towards infatuation, lack of awareness, and power of discrimination at vijñananmaya kośa:

Krodhātbhavati sammohaḥ sammohāt smṛtivibbhramaḥ |

Smṛtibhramśāt buddhināśo buddhināśāt praņaśyati ||

Bhagavad Giįa |2|63 ||

[From anger comes delusion; from delusion loss of memory; from loss of memory the destruction of discrimination; from the destruction of discrimination he perishes (Sivananda, 2013[25])]

Further, vijñananmaya kośa endows manomaya kośa with unending thought processes and wrong cognition which leads to and manifests as adhi (stress) (Nagendra and Nagarathna, 2003[18]). When the manomaya kośa is afflicted, the body follows the disturbance completely. Due to these disturbances, flow of prāṇa in nadis gets vitiated. These imbalances in the flow of prāṇa at the prāṇamayā kośa finally culminate in disease at the annamayā kośa or physical body level [Figure 3]:

Figure 3.

Development of psychosomatic ailments according to ancient scriptures

Citte vidhurite dehaḥ saṅkṣobham upayāti hi |

Saṅkṣobhāt sāmyam utsṛjya vahanti prāṇavāyavaḥ ||

Yogavāsiṣṭha |25|3.35 ||

[When the mind is agitated, the body indeed goes to the state of agitation. On account of agitation, the vital airs (or currents of bioenergy) flow, giving up evenness. (Jñānānanda, 1982[26])]

Management according to ancient scriptures

The question arises: How are the methods and theories of ancient Indian scriptures and the model of PC connected, if at all?

The model of perseverative cognition (PC) proposes the adverse effects of repetitive thinking, either through rumination of the past or anticipatory worry of the future. The model also suggests the predominantly unconscious nature of PC. The ancient model from Bhagavad Gita explains how initial contact with sense objects, later repeated contact with them invokes desire and how that desire is further processed. From the scriptures we can develop a more comprehensive model as follows: a) cause of desire and repeated thinking, b) adverse effects of uncontrolled repeated thinking.

Further scriptures suggest management of uncontrolled repeated thinking. This is by Pratiprasavah (involution), i.e., going back to our original source of existence. It would be worthwhile understanding what this is and how does one do it.

Pratiprasavah (involution), Gunas and Kaivalya

Pratiprasavah (involution) is the most significant technique for restraining mind-modifications. It is the process of involution, where objects merge into their cause progressively, so that ultimately the gunas remain in an undisturbed condition (Satyananda, 2002[21]).

Every individual has a combination of three temperamental characteristics called the gunas: Unactivity (sattva), Activity (rajas) and Inactivity (tamas) (Chinmayananda, 1992[5]; Tapasyananda, 2003[27]). At any one time, one of these natures predominates in the person. When the person reaches the state of kaivalya (liberation), the temperaments revert to their casual state having fulfilled their purpose. Thus the process of pratiprasava or involution of the gunas ends in kaivalya (liberation).

The method of achieving the state of kaivalya (liberation) is proposed in Patañjali yoga sutra through an eight step process called Astanga Yoga (Satyananda, 2002[21]):

puruṣārthaśūnyānāṁ guṇānāṁ pratiprasavaḥ kaivalyaṁ

svarόpapratiṣṭhā vā citiśaktiriti |PYS|4|34||

[Kaivalya is the involution of gunas because of the fulfillment of their purpose; or it is the restoration of purusha to its natural form which is pure consciousness (Satyananda, 2002[21])]

As the sheaths become subtler, there is a progressive influence of consciousness in one’s being, the freedom of operation due to discrimination increases, bondage with the body decreases, and bliss and a feeling of happiness increases.

There are four ways to transcend the kośas, namely, Karma Yoga, Bhakti Yoga, Raja Yoga and Jnana Yoga. Karma yoga is suitable for people of active temperament, Bhakti Yoga for the people of devotional temperament, Raja Yoga for men of mystic temperament, and Jnana yoga for people of intellectual temperament with bold understanding and strong will-power (Sivananda, 1958[24]).

Integrated approach of yoga suitable for modern times

In modern times, an Integrated Approach of Yoga (Nagarathna and Nagendra, 2001[17]) techniques may be a solution to reduce the heightened activity of stress. Healthy yogic diet, Kriyās, loosening exercises and yogāsanas can be used to operate on the Annamaya Kośa (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2010[9]). Practicing proper breathing, Kriyās and prāṇayama help at the prāṇamaya Kośa (Sengupta, 2012[23]; Zope and Zope, 2013[28]). Culturing of manomaya Kośa can be accomplished by relaxed dwelling of the mind in single thought (Dhyāna) (Hoge et al., 2013[6]) and emotion culture by devotional session containing prayers (Lambert et al., 2010[11]; Lambert et al., 2009[12]), Chants, Bhajans, Dhuns and Stotras. At the vijñānamaya Kośa cognitive transformation can take place through lectures and individual counselling (Moritz et al., 2011[16]; Hsiao, 2012[7]). The Ānandamaya Kośa techniques can come under the heading of karma yoga (Kumar and Kumar, 2013[10]), the secret of action. The secret lies in maintaining a present moment awareness, inner silence, and equipoise while we perform all our actions. By regular practice of yoga, one moves from gross state of awareness to the subtle.

Patañjali and the five mental afflictions (kleshas)

Sage Patañjali enumerates five mental afflictions (kleshas): Avidyā (self-ignorance), asmitā (I-feeling), rāga (likes), dveśa (repulsion), and abhiniveśā (attachment to life) as causes for the modification of mind.

Avidyāsmitā-rāga-dveṣābhiniveśāḥ kleśāḥ

|PYS|2|3||

[Ignorance, I-feeling, liking, disliking and fear of death are the pains (Satyananda, 2002[21])]

Sage Patañjali makes two major recommendations: Aṣṭāṅga yoga or the eight-limbed yoga and pratipakṣabhāvana (Sangeetha, 2010[20]). The eight-fold yoga includes: Five self-restraints — yama (non-violence, truthfulness, honesty, sensual abstinence, non-acquisitiveness), five observances — niyama (cleanliness, contentment, austerity, self-study, resignation to god), āsana (seat or meditative posture), prāṇāyāma (regulation of breath), pratyāhāra (withdrawing mind from the objects of sense experiences), dhāraṇa (confinement of the mind to one point or one object or one area), dhyāna (relaxed dwelling of the mind in a single thought with awareness that you are practicing unbroken concentration), and samādhi (becoming one with the artha, that is, the object of concentration).

yamaniyamāsanaprāṇāyāmapratyāhāradhāraṇādhyānasamādhayo’ṣṭāvaṅgāni |PYS|2|29||

[Self restraints, fixed rules, postures, breath control, sense withdrawal, concentration, meditation and samadhi consititute the eight parts of yoga discipline (Satyananda, 2002[21])]

Pratipakṣa bhāvana is the process of sublimating negative thought by invoking opposite positive thought. Suppression will not work, and it may cause rebound effect of thought. The best thing is to sublimate from negativities to the opposite (positive) thoughts (Sangeetha, 2010[20]).

vitarkabādhane pratipakṣabhāvanam |PYS|2| 33||

[When the mind is disturbed by passions one should practice pondering over the opposites (Satyananda, 2002[21])]

vitarkā hiṁsādayaḥ kṛtakāritānumoditā lobhakrodhamohapόrvakā

mṛdumadhyādhimātrā duḥkhājñānānantaphalā iti pratipakṣabhāvanam |PYS|2| 34||

[Thinking of evil thought such as violence, whether done through oneself, through others, or approved, is caused by greed, anger and confusion. They can be either mild, medium or intense. Pratipakṣa bhāvana is thinking that evil thoughts cause infinite pain and ignorance (Satyananda, 2002[21])]

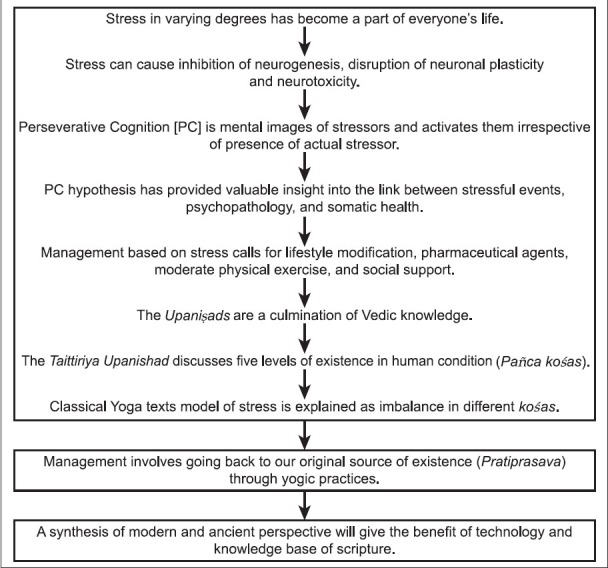

Concluding Remarks [See also Figure 4: Flowchart of paper]

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the paper

It is now clear that for management of stress and related response, focusing at physical and mental levels are not enough. An integrated approach with awareness of the five sheaths (Pañca kośas) that constitute a person is required. With such an approach, it is possible to correct the manifest imbalances in the mind-body complex. Research in this direction has given a positive response in individuals and thus, has provided a base for scientific viability of this five-layer model of a human being (Satyapriya, 2009[22]). A synthesis of modern and ancient perspective will give the benefit of technology and knowledge base of scripture to the stressed. It will also lead a person to higher levels of human emotional and spiritual activity. By adopting this not only can we address stress-related crisis but also ensure good preventive strategies. Thereby we can approach the goal of holistic mental health and well-being.

Take home messages

Uncontrolled rumination/stress (Perseverative Cognition or PC) is the major cause for various psychosomatic ailments.

Mind management is more essential than fighting external causes.

Modern science can gain insights for development of their theories from Indian concepts like the Pañca kośas, Pratiprasava, Aṣṭāṅga yoga (or the eight-limbed yoga) and pratipakṣabhāvana.

Holistic mental health is a potential combatant of modern ailments.

Questions that the Paper Raises

Can the developments of western science and the Indian knowledge base be incorporated into modern health practice?

Will mind-based interventions/therapies like yoga gain more importance in addressing modern lifestyle diseases?

Will modern mental health care system understand and accept the key role of mind?

Will we be able to quantify all levels of kosas?

About the Author

Rajesh S. K. is currently the Senior Research Fellow and lecturer at the S-VYASA, Yoga University, Bengaluru, India. His area of interest is psychology, especially impulsivity, mindfulness, response inhibition, and implicit cognition. He is working on impulsivity and its application to yoga.

About the Author

V. Judu Ilavarasu, is currently a Junior Research Fellow in S-VYASA University, Bengaluru, India. His area of interest is psychology, especially implicit cognition. He is working on developing implicit tool to measure gunas.

About the Author

Prof. T. M. Srinivasan is Dean, Division of Yoga and Physical Sciences S-VYASA, Yoga University, Bengaluru, India. He is the founder member and past president and editor of the International Society for the Study of Subtle Energies and Energy Medicine. He has edited two books: Sense Perception in Sciences and Sastras and Energy Medicine around the World. His area of expertise is Biomedical Engineering, yoga, acupuncture, Tai Chi, Energy Medicine, developing medical devices for holistic health.

About the Author

Prof H. R. Nagendra is Chancellor of S-VYASA, Yoga University, Bengaluru. He has developed many scientifically proven special techniques to manage modern day lifestyle ailments. He is a former Scientist of NASA, and Harvard University Consultant. Presently, he is a Member of the Planning Commission on Health, Govt. of India and Member of NIMHANS Society. He is the present President of VYASA and Chairman of VYASA International. He has published more than 90 research papers on Yoga and its applications and is author of over 30 books in the field of yoga.

Acknowledgement

We thank SVYASA for providing necessary support.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Declaration

This is our original unpublished work, not submitted for publication elsewhere.

CITATION: Rajesh SK, Ilavarasu JV, Srinivasan TM, Nagendra HR. Stress and its Expression According to Contemporary Science and Ancient Indian Wisdom: Perseverative Cognition and the Pañca kośas. Mens Sana Monogr 2014;12:139-52.

Peer Reviewers for this paper: Anon

References

1. Agarwal SK, Marshall GD. Stress effects on immunity and its application to clinical immunology. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Brosschot JF, Pieper S, Thayer JF. Expanding stress theory: Prolonged activation and perseverative cognition. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:1043–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Brosschot JF, Verkuil B, Thayer JF. Conscious and unconscious perseverative cognition: Is a large part of prolonged physiological activity due to unconscious stress? J Psychosom Res. 2010;9:407–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Chinmayananda S. 2nd ed. Bombay: Central Chinmaya Mission Trust; 1992. Taitteriya Upanishad; pp. 150–7. [Google Scholar]

5. Chinmayananda S. Mumbai: Central Chinmaya Mission Trust; 1992. The Holy Geeta; pp. 908–71. [Google Scholar]

6. Hoge EA, Bui E, Marques L, Metcalf CA, Morris LK, Robinaugh DJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: Effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:786–92. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Hsiao YC, Chiang HY, Lee HC, Chen SH. The effects of a spiritual learning program on improving spiritual health and clinical practice stress among nursing students. J Nurs Res. 2012;20:281–90. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0b013e318273642f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Juster RP, McEwen BS, Lupien SJ. Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:2–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Christian L, Preston H, Houts CR, Malarkey WB, Emery CF, et al. Stress, inflammation, and yoga practice. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:113–21. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181cb9377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Kumar A, Kumar S. Karma yoga: A path towards work in positive psychology. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55(Suppl 2):S150–2. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.105511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Lambert NM, Fincham FD, Stillman TF, Graham SM, Beach SR. Motivating change in relationships: Can prayer increase forgiveness? Psychol Sci. 2010;21:126–32. doi: 10.1177/0956797609355634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Lambert NM, Fincham FD, Braithwaite SR, Graham SM, Beach SR. Can prayer increase gratitude? Psycholog Relig Spiritual. 2009;1:139–49. [Google Scholar]

13. Larzelere MM, Jones GN. Stress and health. Prim Care. 2008;35:839–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Larsen BA, Christenfeld NJ. Cognitive distancing, cognitive restructuring, and cardiovascular recovery from stress. Biol Psychol. 2011;86:143–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:873–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Moritz S, Kelly MT, Xu TJ, Toews J, Rickhi B. A spirituality teaching program for depression: Qualitative findings on cognitive and emotional change. Complement Ther Med. 2011;19:201–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR. 1st ed. Bangalore: Swami Vivekananda Yoga Prakashana; 2001. Integrated Approach of Yoga Therapy for positive health; pp. 20–8. [Google Scholar]

18. Nagendra HR, Nagarathna R. 1st ed. Bangalore: Swami Vivekananda Yoga Prakashana; 2003. New perspectives in stress management; pp. 39–47. [Google Scholar]

19. Nagendra HR. The Pa0ñca koças and yoga. In: Ramakrishna RK, editor. Yoga and Parapsychology. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidasss Publishers; 2010. pp. 212–26. [Google Scholar]

20. Sangeetha M. The Rain Clouds of Mind-Modification and the Shower of Transcendence: Yoga and Samadhi in the patanjali yoga-sutras. In: Ramakrishna RK, editor. Yoga and Parapsychology. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas Publishers; 2010. pp. 212–26. [Google Scholar]

21. Satyananda S. 1st ed. Munger: Bihar School of Yoga; 2002. Four Chapters on Freedom. [Google Scholar]

22. Satyapriya M, Nagendra HR, Nagarathna R, Padmalatha V. Effect of integrated yoga on stress and heart rate variability in pregnant women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;104:218–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Sengupta P. Health impacts of Yoga and Pranayama: A state-of-the-art review. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:444–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Sivananda S. 1st ed. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas Publishers; 1958/1974. Sadhana; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

25. Sivananda S. 14th ed. Rishikesh: Divine Life Trust Society; 2013. The Bhagavad Gita; pp. 50–118. [Google Scholar]

26. Jñānānanda B. 1st ed. Pondicherry: Samata Books; 1982. The essence of Yogavāsistha; p. 263. [Google Scholar]

27. Tapasyananda Swami. Madras: Sri Ramkrishna Math; 2003. Śrīmad Bhagavad Gītā; p. 358. [Google Scholar]

28. Zope SA, Zope RA. Sudarshan kriya yoga: Breathing for health. Int J Yoga. 2013;6:4–10. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.105935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]